THE BATTLE FOR BLUEFIELD STATE UNIVERSITY

By Eric Kelderman

JULY 25, 2023

‘HE WAS SINGLING US OUT’

“Lost Souls.”

That’s how Robin C. Capehart, president of Bluefield State University, described “a small oligarchy” of faculty members in his public Substack newsletter last November: “those individuals who are chronically miserable — and aren’t happy unless they’re unhappy.” They “feel entitled to everything,” “don’t hold themselves accountable,” and are “ungrateful” for all of the good things happening at the university, Capehart wrote. Presidents at struggling institutions like Bluefield State often find themselves making the case that sweeping changes, uncomfortable though they may be, are necessary. Many complain privately, or in veiled references, that it’s especially hard to bring faculty around to their agendas. But Capehart, who calls himself “the Campus Maverick,” is openly fighting faculty in a way that few college presidents ever dare.

The newsletter, which has been dominated by Capehart’s pointed commentary on his internal clashes, is the tip of the spear. But the president’s battles with his faculty go beyond public rhetoric. Since he took over the financially struggling historically Black college in the mountains of southern West Virginia in 2019, Capehart has limited professors’ input into several major policy decisions, including new learning objectives and an overhauled post-tenure review process. The university’s governing board, meanwhile, dissolved the Faculty Senate, and replaced it with an assembly subject to new rules and greater oversight from the president.

Some of the professors who challenged Capehart’s reach now argue that he has taken action against them in ways that have damaged their reputations and careers. When several faculty members complained to the university’s accreditor that Capehart had trampled on shared governance and academic freedom, he named them in a universitywide email and took once again to Substack, questioning whether they had committed what he describes as “academic dishonesty.”

The president’s actions and remarks have drawn stinging criticism from academic freedom advocates. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, has warned Capehart he may be violating professors’ free-speech rights and demanded he retract some of his statements. The American Association of University Professors has chastised the president for violating best practices of shared governance.

But Capehart is unapologetic. Bluefield State is an institution in need of policy changes that make it more responsive to students’ needs and hold faculty accountable, he says. The faculty members who are opposing his efforts, he argues, are undermining the institution’s progress and were partly to blame for the precarious financial situation he inherited as president. “Let me just say something about the little faction that you’re talking about. They’re the ones that had a lot of influence over this institution in the previous years,” Capehart says. “You know, during a time in which they had positions of influence,” he adds, “this place was getting darn close, ready to close.”

For now, Bluefield State’s Board of Governors stands behind its “maverick” president. Charlie Cole, chair of the board, says faculty members should more enthusiastically support the president and board’s efforts to remake the institution. “If you share the vision, jump on board,” Cole says. “If you don’t, maybe consider moving to another college or university.”

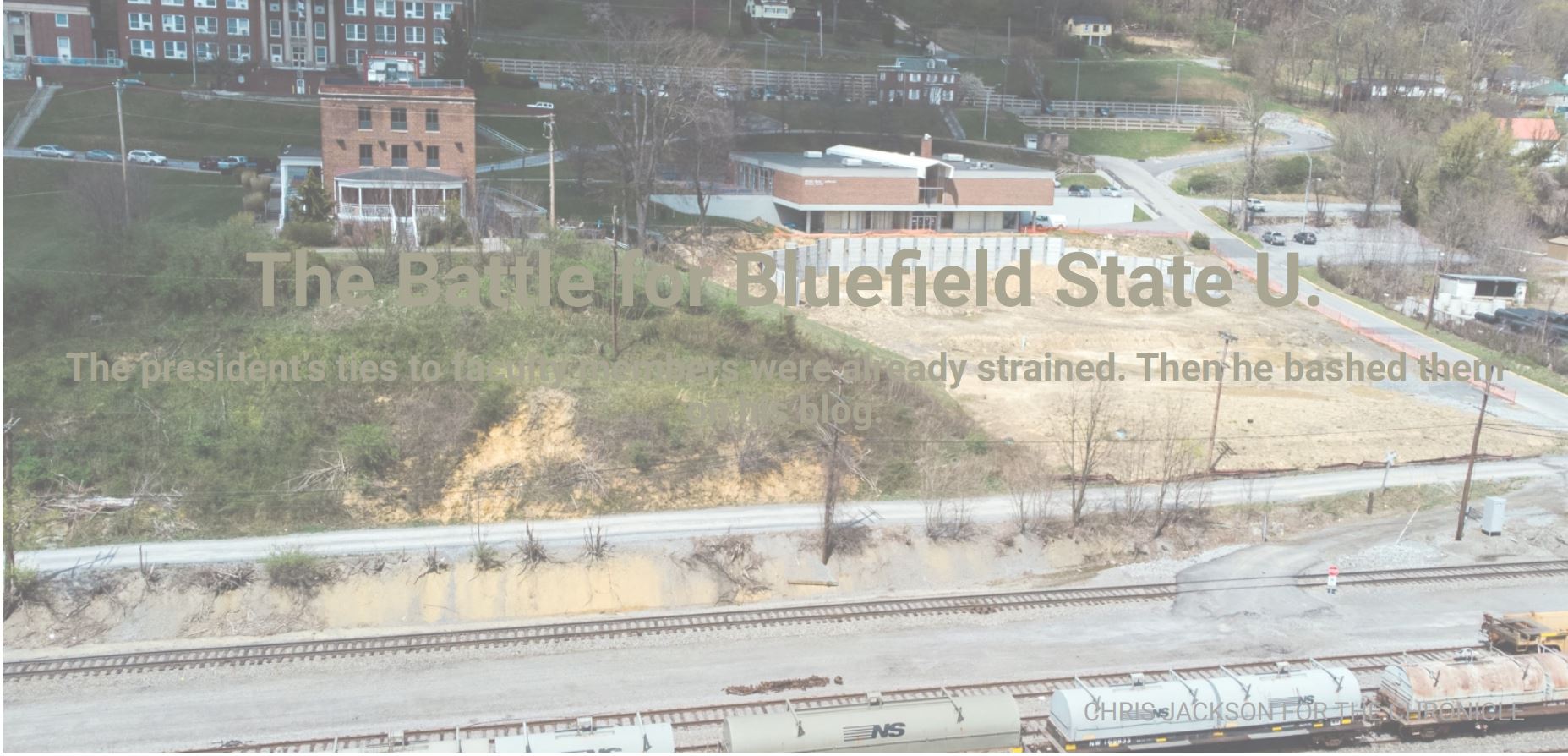

Bluefield State’s campus is just 16 buildings on 34 acres: a narrow strip of land, hemmed in by geography and history. A railroad line cleaves the university from downtown Bluefield, W.Va., and the steep hills of East River Mountain. The location reflects the university’s origins as an institution built to serve a population that was legally and socially cut off from much of the community’s civic and economic life. It was originally a high school, founded in 1895, for the children of Black laborers who migrated there to work in the coal mines. That school, the Bluefield Colored Institute, evolved into a “normal school” to train teachers, and in 1931 it was renamed Bluefield State Teachers College. Twelve years later, it became Bluefield State College.

After the middle of the century, though, the college’s Black enrollment began to shrink as mine workers migrated further north for factory jobs and the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education began to open up opportunities for Black students to attend predominantly white institutions.

White students and faculty grew in number at Bluefield State in the 1960s as the tensions of the civil-rights movement built across the country. The college got its first white president in 1966, sparking protests from Black students who felt they were being pushed out of a college that had been founded for them. Two years later, during Thanksgiving break, a bomb blew up in the gymnasium. Three young Black men were found guilty of conspiracy, but no one was ever charged for detonating the bomb.

No one was hurt by the explosion, but the college’s president permanently closed the dorms, leaving Black students with few options to live near the campus. Over time, the historically Black college found itself enrolling fewer and fewer students of color: By the time Capehart arrived, in the spring of 2019, Black students made up just 7 percent of the student body.

Meanwhile, the college was in crisis. Enrollment during the five years before Capehart’s appointment had plummeted nearly 30 percent, to just 1,266 students. Annual deficits since 2012 regularly exceeded $2 million, according to the college’s audited financial statements.

A 2021 state report, examining the four years before Capehart’s appointment, called Bluefield’s finances “unintelligible and unauditable.” Another, from 2018, labeled Bluefield among the most at-risk institutions in the state and called for consolidation with nearby Concord University. Hired first on an interim basis and then permanently, Capehart began making drastic changes to spare the life of the college.

He began construction on student housing, pledging to reclaim the college’s HBCU legacy and more actively recruit Black students by emphasizing programs that would prepare them for the work force. In 2021 the university acquired a closed hospital, about a mile from campus, that was converted into housing for about 200 students.

“The whole story of the HBCU is giving students the opportunity to have skills that they can come here, get a degree, and walk into work, walk into a job,” Capehart says.

He brought back football, which had been cut in 1980, and Bluefield State saw an immediate increase in the numbers of Black students, as well as international students. By the fall of 2021, Black students made up 14 percent of the enrollment.

He has tried several other measures to expand the campus’s geographic reach, but so far, without success. Capehart’s plan to build the university’s online degree platform, called “B-State Now,” fizzled.

An effort to set up a branch campus in Wheeling, W.Va., nearly 300 miles from Bluefield, was met with outrage by college leaders in that area, who argued the university would be competing with their own offerings. The proposal was later rejected by the state’s Council for Community and Technical College Education, which concluded there was not enough demand for Bluefield State’s programs.

More recently, a bill to allow Bluefield State to offer a wider range of two-year degrees died in the state House of Delegates this year despite overwhelming support in the state Senate and the House Committee on Education.

In his office on campus, Capehart is relaxed and casually dressed. Instead of a suit coat with a university lapel pin, he is wearing a zip-up sweatshirt — though not one repping Bluefield State — more appropriate for his evening plans. After a 90-minute interview, Capehart will head to a rehearsal for a local theater production, where he is part of the stage crew.

Like a growing number of college presidents, Capehart’s background is not strictly academic: He earned a law degree from West Virginia University and a master of laws from Georgetown University. For most of his career, Capehart was a prominent figure in the state’s political and legal establishment, including as secretary of tax and revenue from 1997 to 2000, chairman of the state’s Republican Party, and a Republican gubernatorial candidate in 2004. (He finished third in a close primary.)

Capehart’s office decor includes a plaque commemorating his outstanding teaching award from Marshall University — one of several stops over the past 19 years, which he has spent teaching or leading colleges and universities.

From 2007 to 2015, he was president of West Liberty University, in West Virginia’s Northern Panhandle. He resigned after acknowledging a violation of the state’s ethics code.

In a “conciliation agreement,” Capehart admitted hiring an employee at West Liberty to work for a film-production company he had formed. When Capehart received notice of the complaint and investigation in 2012, the employee was asked to resign from the position at West Liberty. In return for her resignation, Capehart promised the employee a future job at the university, according to the document. At the request of the university’s chief financial officer, the resignation was backdated, according to the findings, to make it appear the employee had quit before the ethics complaint was

received by Capehart.

Capehart paid a $10,000 fine to the state. He says he agreed to sign the document because of the potentially high legal fees to fight the charges. After his appointment at Bluefield State, his run-ins with the faculty happened early. They ramped up when he turned his attention toward overhauling the college’s academic offerings.

In November 2020, the board introduced a draft set of “academic objectives” that Capehart had written without input from any faculty members or even the provost and that had not been made available for public comment, according to a letter to the board from seven faculty members in the university’s social-sciences department.

In response to questions from The Chronicle, the university wrote that the objectives were “a collaborative effort of various professionals at Bluefield State, including the Office of the Provost, and with the opportunity for all faculty to make comments and to discuss the proposal with the Board of Governors.” Ted Lewis, who was provost at the time, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Lewis was recently promoted to lead the university’s branch campus in

Beckley, W.Va.

The proposed objectives were cast as a way to prepare students for “real world success” by focusing on workplace skills, becoming a “knowledgeable member of American Society,” and core competencies that emphasize Western and U.S. history as well as communication skills, mathematics, ethics, and creative and critical thinking. The objectives would replace eight learning outcomes listed in the university’s catalog, which included literacy in information, technology, science, culture, and the arts, as well as critical and ethical reasoning and wellness. The proposed policy would also require the president to report to the board on the “real results that relate to acquiring knowledge and skills and not traditional academic seat-time measures of compliance such as graduation rates, retention rates, progress towards graduation, number of hours or other time-related assessments.” After the draft objectives were posted, faculty members were given a month to provide comments.

Faculty members were dismayed that the people who actually deliver the education weren’t consulted earlier in the process. Typically, advice from the faculty would be considered in crafting such a policy at a public university, not handed to them for comment after most of the work had been done.

“It brings to question why the President would disregard the wealth of knowledge and experience available to him in crafting a policy that will affect the entire purpose and continued existence of this academic Institution,” the seven faculty members wrote to the board.

What’s more, many faculty members were alarmed by the content of the proposed objectives. The students would be expected to understand the “political, economic, philosophical and societal foundations for our country including the history of the United States and western civilization,” and “the fundamentals of entrepreneurship and the free market economic system and a comparison to other major economic systems.”

Some faculty argued that the objectives could be seen as supporting nationalist ideology with minimal attention to diversity, cultures outside the United States, or even Black history.

“We live on a campus with students who still traffic in the ideas of racism and colorism without even knowing it (using words like Negress and colored), blind to their effects and impact,” the seven faculty members wrote in their letter.

Over the faculty members’ loud objections, the board approved the academic objectives policy in January 2021. The panel did make a few changes in response to professors’ concerns, including eliminating the term “American heritage” from a list of core competencies and requiring students earning a bachelor’s degree “to have received an introduction to one or more international cultures through an appropriate curricular, co-curricular or extracurricular opportunity.”

The administration also changed requirements for Black history from “American and West Virginia history includes the development of the African-American community and the role of historically black colleges and universities” to “West Virginia history that includes the development of the African-American community and the role of historically black universities in advancing African-Americans politically, economically and societally.”

Even with the changes, faculty members continue to argue that the objectives are too rigid and constrain faculty from meeting students’ academic needs. The student body at Bluefield State includes a wide range of ages and educational experience, says Julie Orr, an associate professor of nursing. That kind of diversity requires an individualized approach from faculty, she says.

“We can’t deliver a cookbook curriculum.”

Over the course of 2022, the simmering tensions between the president and the faculty reached a boil.

That April, James Quesenberry, a visiting instructor in criminal justice, challenged Darrel Malamisura, a professor of economics and business law, for his seat as chair of Bluefield’s Faculty Senate. Quesenberry, who had taught for two years at the university, said the senate was “nothing more than a gripe session, talking about things that didn’t matter,” with only a few people blaming all of the university’s problems on the administration.

Members of the Faculty Senate were concerned that an instructor with the title visiting faculty had been nominated to be chair, according to accounts from several faculty members who spoke on background. (Typically, visiting faculty were allowed to be members of the senate only when a department didn’t have enough tenured faculty members to serve.)

Instead of allowing Quesenberry to run for chair, the senate ousted all four visiting faculty members who were members of the senate. The Board of Governors requested an investigation. In September 2022, Brent D. Benjamin, Bluefield State’s general counsel, provided a written report to the board, arguing the senate had violated its own procedures as well as the state’s open meetings laws. Benjamin’s report named Malamisura, who had been re-elected as chair of the Faculty Senate, as the primary actor in removing visiting faculty from the senate membership and elections — actions he described as a “serious departure from West A Virginia law, the Board of Governors’ policies, the Faculty Handbook and the Faculty Senate Constitution.”

At the September meeting of the board, its chair, Cole, nullified the Faculty Senate elections, though the elected vice chair continued in his role. In November, the entire board voted to dissolve the senate altogether, replacing it with a Faculty Assembly open to all instructional staff. The board directed Capehart to write the assembly bylaws with “input from the faculty and such others as he deems necessary.”

Faculty members say they were not consulted on the bylaws for the new assembly. It the same time the board and Capehart were replacing the Faculty Senate, they were also adding new requirements for tenure and a new post-tenure review process, again drafted without input from faculty members, according to Amanda Matoushek, an associate professor of psychology, and several

other faculty members. As with the academic-objectives policy, the university described the post-tenure review policy as “a collaborative effort of various professionals at Bluefield State, including the Office of the Provost.”

Many faculty objected to the new process, they said, because it replicates the tenure process and is also very similar to the annual performance evaluations. Both the tenure and the post-tenure reviews require faculty members to meet the standards for the same 11 criteria, such as “excellence in teaching,” “distinctive professional and scholarly activities and recognition,” and “ significant service to the community and the people of West Virginia.” The annual performance review requires meeting 10 of those same 11 standards.

“While tenure has not been abolished, having to meet the same criteria and submit the same materials as required for initial award of tenure renders the word ‘tenure’ meaningless,” Matoushek wrote in a letter to the board protesting the policy after it was proposed.

In addition, under the new policies, tenured faculty are now responsible for recruiting students to their program at the university — a mandate that is rarely, if ever, imposed as a condition of tenure, though it may sometimes be expected informally or as part of a job description, according to several higher-education-policy experts. Several Bluefield State faculty report they are seeking clarification from the university on how this will be assessed.

In a written statement, the university responded that it “does not agree that a ‘demonstration of active recruitment of students for his or her field of study’ is a ‘highly unusual’ consideration in tenure and post-tenure reviews.” The AAUP condemned the university’s leaders for ignoring the best practices of shared governance in both the way they developed the post-tenure review and the design of the review process itself. “It would be inappropriate for an administration or governing board to unilaterally establish a formal system of post-tenure review,” the association wrote of Bluefield State’s policy.

Capehart says tenure has not ended at Bluefield State: “All we said was, if you do not fulfill those [standards] you will automatically be put on an improvement plan to try to elevate yourself to these standards,” he said. “Now, have you heard that from those people? No, they didn’t say anything like that to anybody.” In early November 2022, faculty members approved three no-confidence resolutions — one each for Capehart, Benjamin, and the board — over a long list of complaints, including the approval of the academic objectives, the new post-tenure review policy, and the dissolution of the Faculty Senate.

The faculty approved all three motions, with more than 70 percent voting in favor of each no-confidence resolution.

“President Capehart’s recent administrative actions … exhibit a general contempt for the faculty themselves, their voices, their knowledge, their experience, their elected representatives on the Faculty Senate, and their fundamental importance to the university,” the no-confidence resolution said. “His actions have created a toxic work environment of fear, discord, and distrust among the faculty.”

The following month, Capehart began writing his Substack newsletter — which he named “The Campus Maverick” — promising to “discuss the manner in which my experiences in the private sector and public sector has (sic) shaped me into a ‘maverick’ in the world of higher education,” Capehart wrote.

But after a Thanksgiving post touting his accomplishments, the tenor turned. In a follow-up post, Capehart took aim at a faculty member he said had responded negatively to the Thanksgiving message, someone he described as “one of the small group of faculty members who pushed a ‘no confidence’ vote … by peddling false narratives and ignoring the advancements made in the past four years.”

Capehart added that “higher education is uniquely endowed with more than its share” of such people — the “lost souls” — whom he described as feeling “entitled to everything,” “infallible,” and “spiritually disconnected.”

“‘What’s God got to do with it?’” he imagined they’d say. “‘I’ve done it all myself.’”

“They attract other miserable people,” Capehart wrote. “They gather in a toxic bubble to talk about how bad things are. Misery truly loves company.”

he disparaging blog posts weren’t all the faculty had to worry about. Several faculty members who were prominent in the no-confidence votes and the Faculty Senate fight say they began to face disciplinary actions and increased scrutiny from the president.

In November 2022, Rodney Montague, who had been vice chair of the senate during the previous semester, gave a class lecture about the Peloponnesian War. He used profanity to portray the difference between the two factions: the Athenians and the Spartans.

Montague, professor of history and “faculty member of the year” in 2020, says he was trying to show students how the Spartans despised the Athenians for becoming soft and abandoning traditional values of strength and virtue. The goal was to give the Spartans “a roguish gang-like attitude, he says, as if they were speaking amongst themselves.” He admits he cursed — he used roughly 15 obscene words over five minutes — but says he didn’t use any words that would have touched on race or gender.

A first-year student recorded part of the lecture and brought it to Capehart, who initially sought to have Montague fired, according to Matoushek, who was chair of the social-sciences department at the time. “I provided them some background and pedagogical work showing how the use of strong language was appropriate,” says Montague, one of only two tenured African American faculty members at Bluefield State. “Nothing I did was random.”

Though the fall semester was nearly finished at that point, Capehart ordered an investigation and removed Montague from teaching, Matoushek says.

Capehart’s decision to suspend Montague happened just days before the start of the university’s five-week “intersession,” she says, forcing administrators to scramble toreplace Montague for the course he was scheduled to teach. Montague continued to receive his regular salary, but not an extra $1,650 for the intersession course.

In December, an inquiry by the provost, the dean of social sciences, and Matoushek concluded Montague should not have been suspended, Matoushek wrote in an email to The Chronicle. None of the students who spoke with that group said they were offended by the profanity, she says, and some even appreciated that they were being treated as adults.

Those findings were shared with the president the week before Christmas. But in early January, just a few days before the start of the spring semester, the board decided to extend Montague’s suspension for another 30 days while the university’s lawyers considered the matter.

That again forced a scramble to find a replacement for Montague, who was scheduled to teach five courses, including one on African American history. Meanwhile, an adjunct was assigned to teach a course on the history of hip-hop music, says Matoushek.

“All of this was over the use of profanity in the classroom,” Matoushek wrote in an email, yet “the newly created hip-hop history course includes listening sessions. … Do artists like N.W.A. not use profanity in their songs?”

The board waited until a late-February meeting, nearly six weeks after the start of the semester, to vote to reinstate Montague.

The university declined to respond to questions or confirm any details about the events or the procedures it followed in disciplining Montague, writing that “Bluefield State does not comment on specific matters involving employees and their employment.”

In an April interview, Capehart told The Chronicle that he liked Montague but was concerned about the reputation of the institution. “What’s going to happen when that parent of that child, when he goes home and plays that to his dad?” Capehart says of his decision to suspend the professor over the classroom recording. “Because he certainly wouldn’t play it to his mom.”

Robin Capehart took the reins at Bluefield State in 2019.

“I don’t really care what other institutions do,” Capehart says. “What are those parents going to think about sending their child to this school?”

Throughout the process, Montague says, he received nothing in writing about his suspension or any of the decisions regarding his employment. “They made up whatever procedure they felt was best,” he says. Montague says he now feels like he’s under surveillance. The entire episode has made him wary of the university’s administration.

“I’m not sure whether they value what we do here or not,” says Montague. “I lost my chance to teach my African American history course here at an HBCU. What does that tell you?”

Throughout the fall of 2022 and early 2023, Capehart’s Substack newsletter — begun as a way for him to explain his nontraditional campus-management style — became a cudgel in his mounting fight with the faculty.

While institutions are loath to discuss personnel matters publicly, Capehart couldn’t resist using his platform to question whether academic freedom should really apply to Montague’s lecture — though he didn’t use the professor’s name — which he called a “serious, sexually-oriented outburst that allegedly heightened the level of discomfort among, in particular, female students.”

In January, he waded into accreditation standards the university must meet on academic freedom and opined that “it’s hard to see anything short of a tortured definition of ‘academic freedom’ that would include unfettered utterances and obscene rants in the classroom.”

By then, accrediting standards were an issue for another reason: Malamisura, Matoushek, and two others filed a complaint with the university’s accreditor, the Higher Learning Commission, listing the same arguments that had been enumerated in the no-confidence resolutions.

In its response to the accreditor, the university blamed the Faculty Senate and those who submitted the complaints for “the dissemination of false and misleading information.”

Soon after Bluefield filed its response, the commission found the university was not out of compliance with any accreditation standards. The accreditor’s response didn’t comment on the veracity of the complaints.

Then, in an open email to all Bluefield employees, Capehart released the names of the faculty members who had complained to the accreditor, writing they had “challenged recent actions by the Board of Governors to improve the University with its accrediting body.”

Faculty members are free to air their criticisms, Capehart said during an interview, but the complaint to the accreditor included information he described as “just not true,” such as the accusation that faculty had not been given a voice on the academic objectives and post-tenure review process. Faculty were given that opportunity after those measures had been drafted, he says, rather than having been involved in developing them.

Capehart also argued that the complaint put the university’s accreditation at risk — even though few colleges ever lose accreditation, particularly not over shared governance violations. “It was obvious he was singling us out,” says Malamisura, who likened Capehart’s naming of faculty in the email to outing whistleblowers.

Matoushek says several friends and colleagues called to share their concern that she was on the verge of being fired. “I definitely felt I was being targeted,” she says, “then he put out the blog post that he wanted to fire me.”

In that Substack post, which was illustrated with a lying-face emoji, Capehart questioned whether the faculty members who complained to the accreditor could be fired if “the accusations are premised with no less than pure falsehoods.”

“At our institutions as with most, academic dishonesty is grounds for dismissal.

However, to do so will undoubtedly bring cries of ‘retaliation’ and the obligatory filing of grievances,” he wrote.

“If you are truly dedicated to maintaining the credibility of the institution,” Capehart added, “the imposition of some form of disciplinary action is necessary.” That kind of language set off alarm bells for organizations that defend free speech and academic freedom. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression sent a letter to Capehart, saying there was no legal notion of “academic dishonesty” and warning that any action to dismiss faculty for their criticisms may violate their free-speech rights.

“We remind you that a public college administrator who violates clearly established law will not retain qualified immunity and can be held personally responsible for monetary damages for violating others’ First Amendment rights,” the foundation

wrote.

Capehart said the criticism of his Substack musings, by FIRE and by his own faculty, is mistaken: He didn’t mean to threaten anyone’s job by his comments questioning whether there were limits to academic freedom. “I was just raising the question,” he said, “should they, could they be held accountable? We’re not doing anything. We’re not firing anybody because of it.”

Meanwhile, the fallout has continued, say Malamisura and other former members of the Faculty Senate.

This spring Malamisura and two other tenured faculty members in the business school, including one who had been tenured less than three years, were required to undergo the new post-tenure review.

Late in the spring semester, Capehart rejected the provost’s recommendation to approve the post-tenure review of Malamisura and Michelle Taylor, an associate professor in the business school, a former member of the Faculty Senate, and an open critic of Capehart.

“We have found issues with your credentials which have a negative effect on our accreditation from the HLC (Higher Learning Commission) and the ACBSP (Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs),” said Capehart’s letters to Malamisura and Taylor.

Malamisura has a bachelor’s degree from Bluefield State, an M.B.A. from St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, and a law degree from Ohio Northern University. Taylor, who was granted tenure in 2020, has a bachelor’s degree and an M.B.A. from West Virginia University and an education doctorate from Benedictine University, in Illinois.

Though it’s not clear from the very short letter, the university appears to be questioning whether their credentials are appropriate for the courses they teach. Through a spokesman, the university declined to comment on the matter, including why the credentials of Malamisura and Taylor weren’t an issue when the Higher Learning Commission completed its full accreditation review of Bluefield State in July 2022. Under the university’s policy, both faculty members would retain their positions but be subject to a performance-improvement plan, according to the president’s letter.

Taylor is Bluefield State’s other tenured African American professor, besides Montague, and is among the small percentage of faculty members who are persons of color. Her husband, who taught undergraduate courses in accounting for more than four years as a visiting instructor at Bluefield State, did not receive a contract offer for the fall.

Another former member of the Faculty Senate, also a person of color, lost her tenuretrack position with the university with no explanation, according to a letter from Capehart obtained by The Chronicle. Debjani Chakrabarti, who was in her fifth year of teaching, had been promoted to associate professor of sociology for the 2021-22 academic year but had not yet applied for tenure.

In March, Capehart notified Chakrabarti, who identifies as Asian American, that her contract would not be renewed.

According to emails and documents obtained by The Chronicle, the university declined to reconsider that decision despite letters of support from students, other faculty members, and Sarita A. Rhonemus, the associate provost, who has since been named interim provost at Bluefield State.

Chakrabarti “is an accomplished and dedicated associate professor who has made significant contributions to the University’s teaching and learning mission,” Rhonemus wrote in an April 6 letter to Capehart.

The university declined to comment on Chakrabarti’s employment. Chakrabarti, Malamisura, and Taylor have all filed grievances with the state’s Public Employees Grievance Board. Several other tenured and tenure-track faculty members still do not have completed contracts for the fall semester. In her filing to the grievance board, Chakrabarti wrote that she had been “experiencing discriminatory and hostile working conditions for a number of years, and especially since the 2022 no-confidence vote(s).”

“The action by Bluefield State University comes as retribution and retaliation after retaliatory threats,” states Chakrabarti’s grievance.

At a July hearing on Malamisura and Taylor’s grievances, the university provided no explanation or documentation for questioning the professors’ credentials, according to an email from Taylor.

Malamisura says he is taking courses to become a certified public accountant in case his contract is not renewed. He feels the entire situation is related to his role as a critic of Capehart.

“It’s stressful,” Malamisura says. “Every time I turn around, he’s coming after us.”

Despite the controversies that have enveloped Capehart’s leadership, Bluefield State’s finances have improved during the president’s tenure. Capehart revised the college’s budgeting process after alerting lawmakers in 2019 that its internal financial controls were sloppy. Revenues have increased, mostly from federal Pell Grants and coronavirus-relief money, which grew from $3.3 million in the 2020 fiscal year to $7.4 million in 2021 and nearly $10 million the following year. The number of full-time faculty increased from 63 to 73 between 2020 and 2022, according to state figures. The number of nonclassified staff has also increased over that period, from 48 to 81.

Results for the current fiscal year may not be as sunny. In February, the university’s chief financial officer, James Ronald Hypes, told the board the administration was working on a reorganization to make the institution more efficient, according to minutes from the meeting. The budget “is close,” Hypes told the board, “and we will break even.”

Capehart says he doesn’t understand the reaction to his leadership and the newsletter posts. He also insists the amount of faculty opposition is small — just a handful of people who are responsible for riling up discontent.

Orr, the nursing professor who is now chair of the Faculty Assembly, disputed that characterization: “It depends on the size of the hand.” In this case, she says, “it was a large handful.”

If the president and board are trying to force out faculty who disagree with the leadership, she says, it’s not going to be easy to replace them. “We are teaching at a small institution in a small town, and many faculty are not anxious to come to a town this size,” she says.

One faculty member, Sean P. Connolly, has already resigned his position because of the turmoil. Connolly was a professor of humanities and director of the university’s honors college. He was also one of the four who filed the complaint with the Higher Learning Commission.

In an email, Connolly wrote that more faculty members would speak out but that they fear retaliation and financial consequences in a state without strong union protections. In May, Connolly began working as an analyst with the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

A recent survey of employees at Bluefield State found that more than 40 percent of the faculty feel they “rarely” or “never” have sufficient opportunity for input on a decision that affects their duties and responsibilities. An additional 10 percent say they have that opportunity only “sometimes.”

Nearly 40 percent of faculty “disagree” or “strongly disagree” that they can express concerns about decisions or situations without fear of reprisal.

Those faculty members will have a chance to air their concerns more widely in the fall. The Higher Learning Commission has scheduled a “focused visit” to the university in late September to follow up on a second set of complaints from Bluefield State employees.

In an April 7 letter, the accrediting agency wrote to Capehart that it will be considering whether the university is meeting the requirement to “ensure fair and ethical behavior on the part of its governing board, administration, faculty and staff.” Deirdre Guyton, director of alumni affairs and the staff representative on the board, says Capehart’s public newsletter posts were not helpful. But she attributed the tensions to faculty members who are airing the university’s problems to the media.

“You know, as an HBCU, and how we were founded on Christian principles and family, we just don’t do that,” she says. “We don’t air our dirty laundry.” Some faculty are more concerned about the impact of the infighting than about Capehart’s plan to make the university more responsive to work-force needs.

“If you get distracted by governance for too long, says Philip D. Schall, an associate professor of computer science, “you’re going to realize you don’t have a school anymore.” Capehart’s Substack newsletter has been dormant since February, and the new Faculty Assembly finally elected leaders, after some abortive efforts to do so, in April. (James Quesenberry finished a distant second in the election for chair and third in the election for vice chair.)

Still, Guyton and Schall’s hopes for better communication between university leadership and the faculty appears dim.

In May, the board scheduled a meeting with the assembly to hear the faculty’s concerns about how Bluefield is being run. The board members — except for the chair, Charlie Cole, who didn’t attend — were lined up at a table at the front of the room, says Matoushek. She compared it to a firing line.

The meeting started at 3 p.m. One faculty member raised a question about the construction site for a dormitory project that was never completed. Other faculty members had questions, Taylor says, but when no one jumped in immediately, Capehart quickly adjourned the session.

“It was essentially a pointless meeting,” Matoushek says, “because nothing was discussed.”